Rethinking the McGill Big 3: From Spine Sparing to Confidence Building in Low Back Pain Rehab

“Your spine isn’t fragile — but the way we talk about it might be.”

Why This Topic Matters

Lower back pain (LBP) remains the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide (Vos et al., 2021). Despite decades of research, the clinical outcomes for chronic and recurrent LBP are still poor — and part of the problem may be the way we coach, cue, and conceptualise the spine itself.

Many clinicians, coaches, and physios still rely heavily on the McGill Big 3 exercises — a structured, biomechanics-driven approach designed to “spare the spine” through specific core endurance movements. While these exercises have their place, they are often delivered with fear-based narratives, which can unintentionally reinforce fragility, limit movement, and delay recovery.

This blog unpacks:

What the McGill Big 3 were designed to do

How their use has evolved — or stalled

The danger of nocebo (worsening symptoms or negative side effects because they expect to — not because of an actual harmful substance or treatment) language and “spine-sparing” myths

How pain science reframes spinal rehab for better long-term outcomes

The McGill Method: A Structured Biomechanical Framework

Dr. Stuart McGill is a respected researcher in spinal biomechanics. His work focuses on minimising shear forces and improving trunk stability through specific, controlled movement. His approach assumes that:

Back pain is largely mechanical in origin

Poor movement patterns or instability are primary drivers

Spinal motion, particularly flexion and rotation, should be minimised during rehab

To address this, he developed a core protocol based around three movements:

The McGill Big 3:

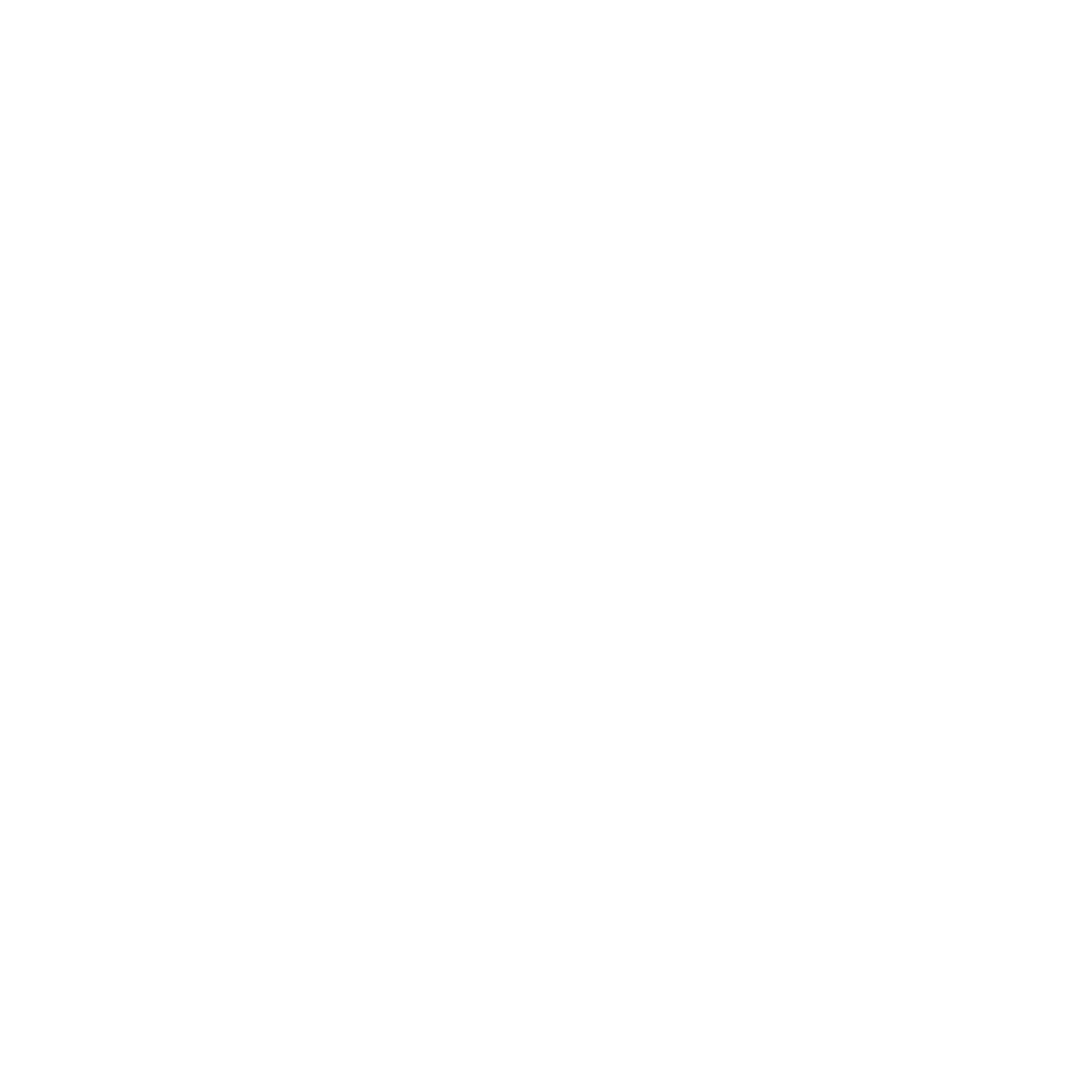

Modified Curl-Up

Designed to activate the anterior core without lumbar flexion.

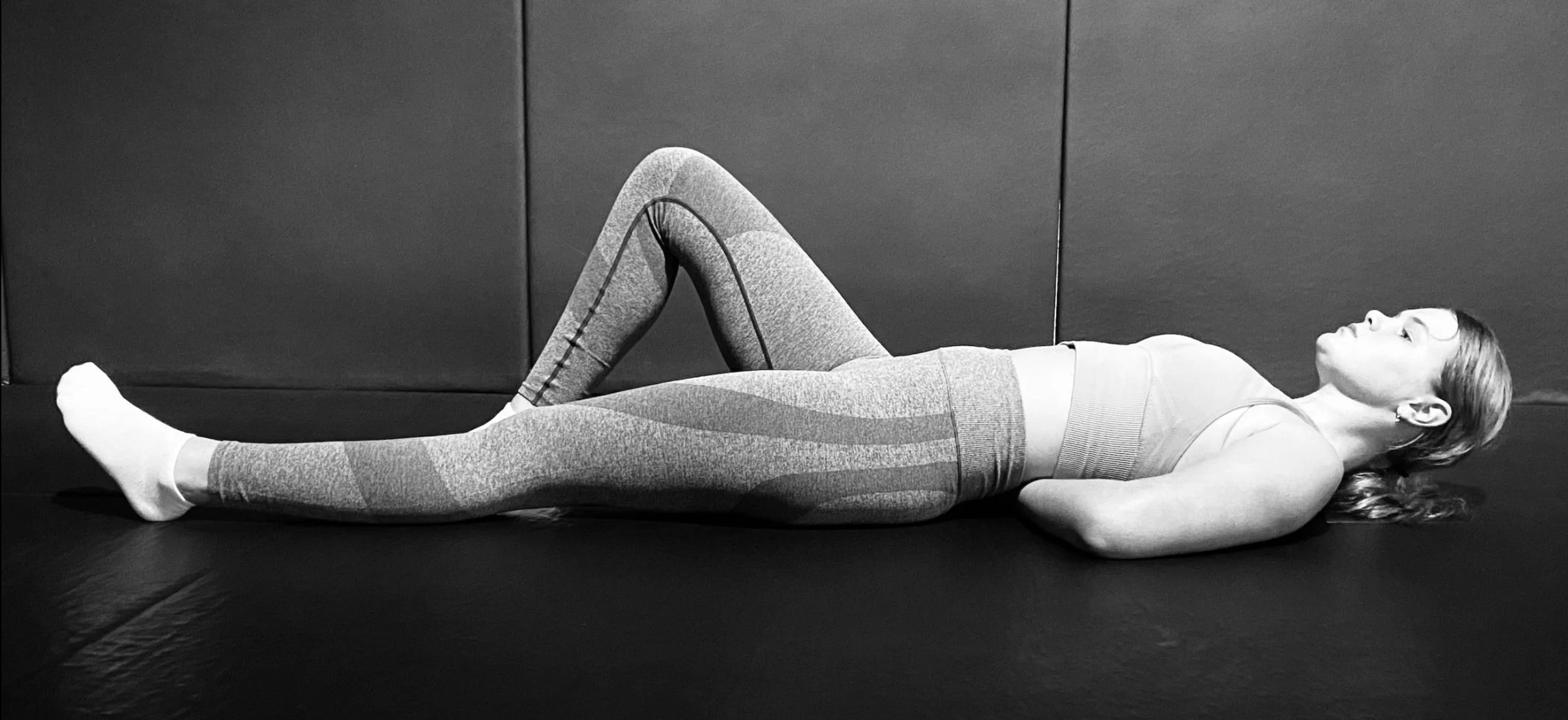

2. Side Plank

Builds lateral trunk endurance with minimal spinal loading.

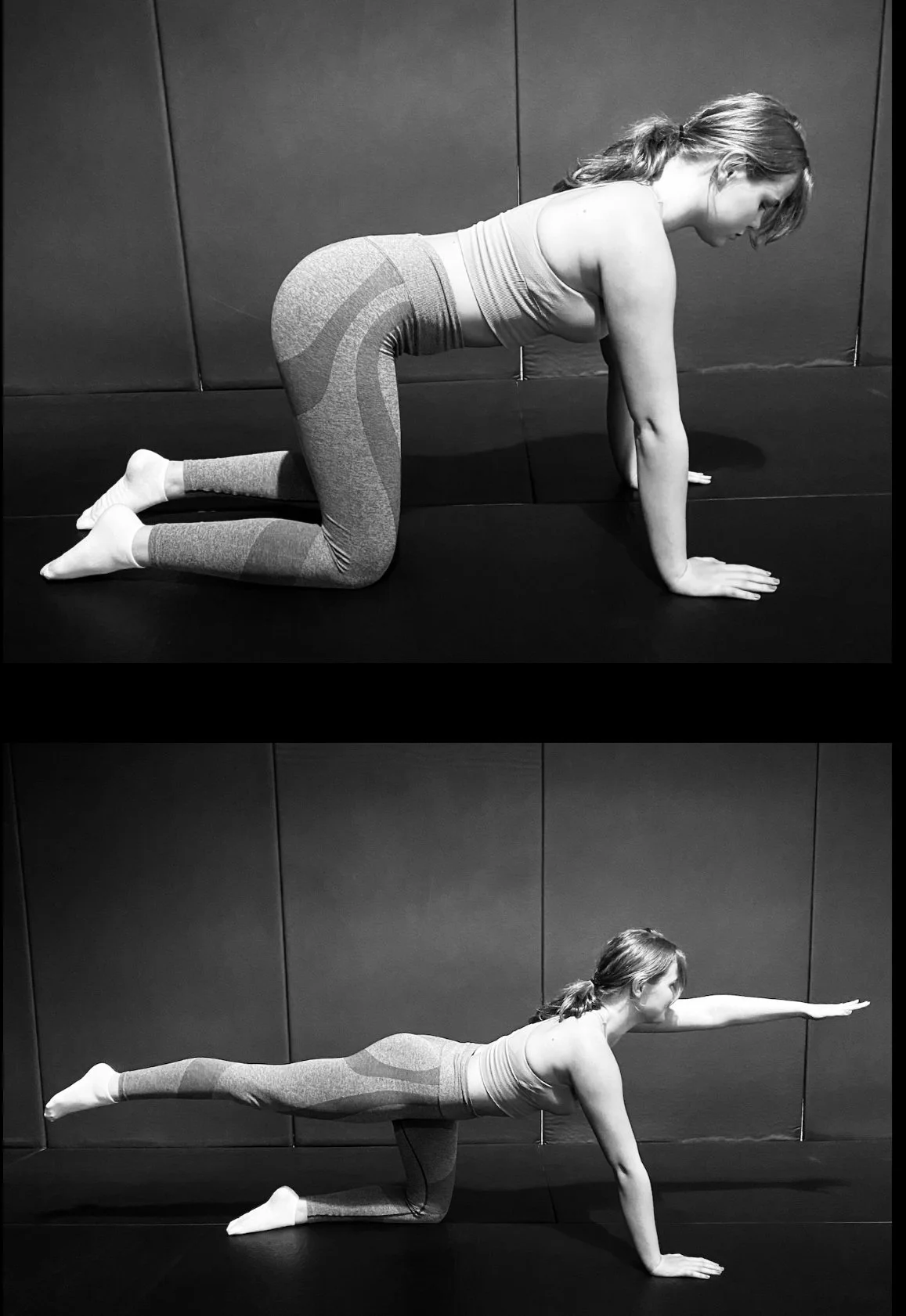

3.Bird Dog

Encourages contralateral coordination and core stability in a neutral spine.

These are low-load, high-endurance movements meant to build core control in a “safe” range of spinal motion — typically neutral. In acute cases, this can be appropriate. But problems arise when this becomes the end goal, rather than a stepping stone.

The Problem: From Protection to Paralysis

The core concern isn’t with the exercises themselves — it’s the way they’re often delivered. Many clinicians unintentionally wrap the McGill Big 3 in language that implies danger, such as:

“You must avoid spinal flexion.”

“Brace your core every time you move.”

“Neutral spine is the only safe position.”

“Your back is vulnerable and needs protecting.”

This type of cueing creates nocebo effects, where negative expectations worsen a patient’s perception of pain and risk. These beliefs lead to:

Over-bracing and tension during even simple tasks

Avoidance of daily movements like tying shoes or lifting children

Long-term fear of exercise or varied movement

Reduced function and self-efficacy

“When patients become more afraid of bending than they are of pain itself, we’ve created a bigger problem.”

A Modern View: Pain Science and the Biopsychosocial Model

Contemporary pain science redefines how we understand low back pain. Instead of blaming structure alone, we now know that pain is:

An output of the brain and nervous system, not just a symptom of tissue damage

Modulated by beliefs, stress, expectations, and context

Often disproportionate to structural pathology

This means that a client with disc degeneration on MRI may be pain-free — while someone with no visible damage may be highly sensitised and in chronic pain.

Key takeaways:

Pain ≠ damage

Imaging ≠ diagnosis

Flexion ≠ harm

The meaning we attach to movement matters more than the movement itself

The Social Media Effect: When Posture Becomes Performance

Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok have played a major role in spreading rigid spinal dogma. Influencers and trainers frequently demonstrate:

Bird dogs with dowel rods to prove “neutrality”

Core workouts focused entirely on anti-rotation and bracing

Warnings against flexion under any circumstances — even bodyweight

While these videos may look professional, they promote aesthetic perfection over functional variability. The average person starts to believe:

“If I don’t look like that, I’ll get injured.”

“I must brace my core constantly to be safe.”

“Rounding my back is dangerous.”

This turns the gym floor into a stage — not a rehab environment — and alienates the very people who need to move freely again.

Clinical Case Study: Rebuilding with Confidence, Not Bracing

Patient: 42-year-old recreational runner and desk-based professional

Presentation: Ongoing LBP for 9 months, no red flags. Fears flexion and avoids tying shoes, squatting, or twisting.

Previous advice: “Keep your spine neutral at all times” and “brace before every movement.”

Initial phase:

Performed McGill Big 3 with excessive tension and anxiety

High levels of fear and constant symptom monitoring

Belief that flexion would “damage” her spine further

Intervention:

Education: Pain doesn’t equal damage; flexion is safe

Movement: Introduced loaded hip hinges and gentle lumbar flexion

Language: Switched from “protect” to “rebuild,” “adapt,” and “progress”

Outcome:

Returned to running with a 90% reduction in pain within 8 weeks

Regained confidence in squatting, deadlifting, and playing with her children

Ceased all “bracing drills” in daily life

“The turning point wasn’t a new exercise — it was a new narrative.”

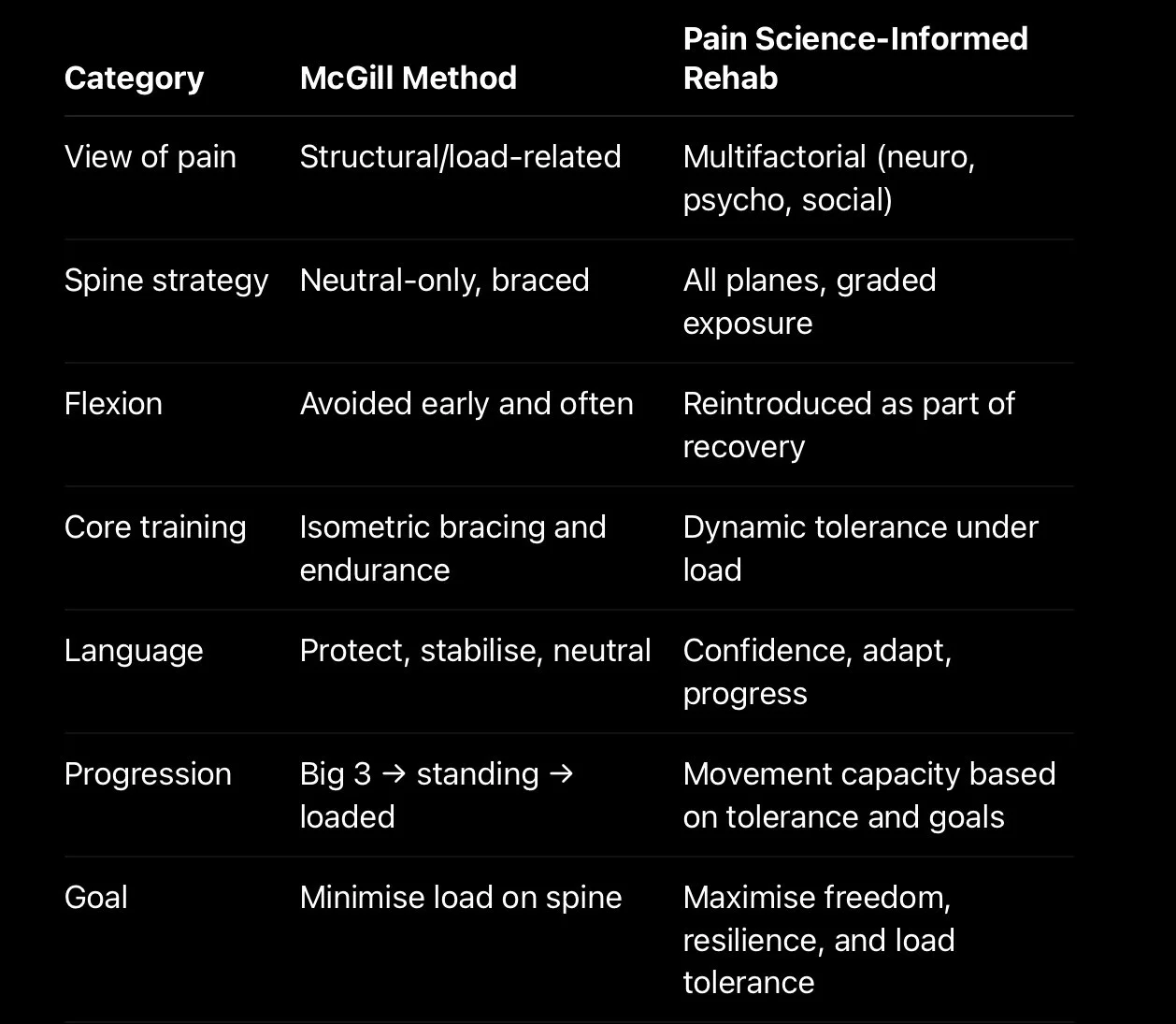

Comparison Table: McGill Method vs. Modern Pain Science Rehab

Coaching Movement Beyond the Big 3: A Phase-Based Approach

While the McGill Big 3 can serve as a useful starting scaffold, they must not become the ceiling. Here’s how to structure a phase-based, confidence-building approach to spinal rehab.

Phase 1: Acute Pain or High Sensitivity

Goals: Reduce threat, introduce movement, restore control

Useful if: Client is highly fearful, in acute flare-up, or deconditioned

Strategies:

Use Big 3 briefly and with reassurance, not rigidity

Begin light spinal mobility: cat-cow, pelvic tilts, breathing drills

Use language that validates their pain but dismantles fear (e.g., “Your back is sensitive, not damaged”)

Reassure: “We’re not avoiding movement — we’re reintroducing it on your terms.”

Phase 2: Tolerance and Exposure

Goals: Build variability, resilience, and load capacity

Useful if: Client has reduced pain but avoids specific movements or fears “bad form”

Strategies:

Add loaded movements: kettlebell deadlifts, front-loaded squats, offset carries

Reinforce: “Your body gets stronger with what it practices”

Rotate between tasks involving flexion, extension, rotation, asymmetry

Reduce cueing — let the patient feel their own movement again

Phase 3: Return to Real Life and Autonomy

Goals: Empower independence, confidence, and load robustness

Useful if: Client is mostly pain-free and ready to challenge variability

Strategies:

Recreate life or sport tasks: bending under fatigue, awkward lifting angles, floor transitions

De-emphasise “perfect form” — encourage adaptability

Remove the “rules” that were useful in Phase 1

Empower: “You’re in control — your body knows what to do.”

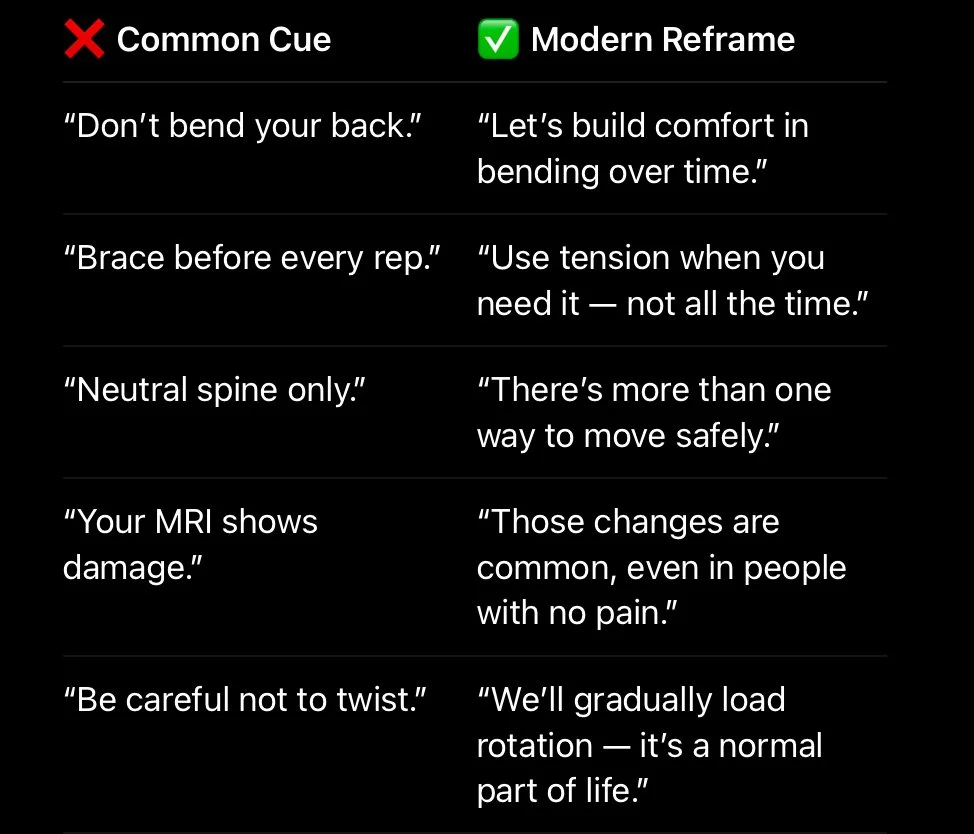

Real-World Language Shifts: What to Say Instead

Language is one of the most powerful tools in spinal rehab — for better or worse. Here are practical clinical reframes to use immediately:

Research Recap: What the Literature Actually Says

Clinicians are often surprised by how little imaging and posture correlate with actual pain. Here are some key findings to know — and share with patients:

Brinjikji et al. (2015): Over 60% of asymptomatic adults over age 40 show disc degeneration, disc bulge, or facet arthropathy on MRI.

Wertli et al. (2014): Fear-avoidance beliefs and catastrophising are more predictive of chronic LBP than structural pathology.

O’Sullivan et al. (2018): Cognitive-functional therapy (addressing beliefs, movement habits, and exposure) yields better long-term outcomes than manual therapy or bracing.

Caneiro et al. (2021): Variability, strength, and confidence in movement predict sustained return to function better than rigid form or “core control.”

The message is clear:

The spine is strong. Beliefs are modifiable. And recovery isn’t about protecting people — it’s about progressing them.

Case Study 2: Overcoming the “Brace or Break” Mentality

Client: 39-year-old police officer

History: 2-year history of episodic LBP, aggravated by rotation and fatigue

Belief: “I need to brace before getting in and out of the car or I’ll go into spasm.”

Assessment findings:

Over-tense during most movements

High protective strategy around flexion and side bend

Strong but hypervigilant

Rehab strategy:

Movement exposure under fatigue (timed get-ups, carries, squats)

Reduced “brace-first” habits through education and breathing techniques

Introduced flexion + rotation with load (e.g., rotational sandbag lifts)

Outcome after 10 weeks:

Returned to full duties without flare-ups

Reported less stiffness after long shifts

Stopped using rigid bracing in everyday tasks

“You helped me stop overthinking and start moving like myself again.”

Best Practice Summary for Clinicians

If you’re integrating McGill-style rehab with modern pain science, keep the following clinical principles top of mind:

Do:

Use the Big 3 as a low-threat intro — not the entire plan

Reassure patients that their spine is strong, not broken

Reintroduce flexion, rotation, and loaded movement early when tolerated

Focus on beliefs, not just biomechanics

Track function, not just pain levels

Avoid:

Rigid rules like “always brace” or “never bend”

Over-prescribing neutral spine without reason

Posture correction as the primary goal

Language that implies fragility or danger

Creating dependency on specific drills or techniques

Final Thoughts: Beyond Bracing, Toward Capability

The McGill Big 3 can still play a role in low back pain rehab — but only when used intelligently and temporarily. As clinicians, we must stop asking “what’s the safest way to move?” and start asking “what’s the most adaptable way to load this person?”

Rehab should:

Reduce fear

Build capacity

Restore trust in movement

Help people return to bending, twisting, lifting, and living

The goal isn’t to preserve a neutral spine — it’s to help someone carry their grandkids, row a boat, run a 5K, or garden without fear. We need to move away from narratives of protection, and toward a language of resilience.

“Spines aren’t fragile — they’re anti-fragile. They get stronger with use, not weaker.”

Let’s stop scripting rehab like a performance. Let’s start coaching people to move forward with confidence.

References

Brinjikji, W., et al. (2015).

Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations.

AJNR American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(4), 811–816.

https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4173Wertli, M.M., et al. (2014).

Catastrophizing — a predictive factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: a systematic review.

The Spine Journal, 14(11), 2639–2657.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.037O’Sullivan, P.B., et al. (2018).

Back to basics: 10 facts every person should know about back pain.

British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(24), 1548–1549.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099611Caneiro, J.P., et al. (2021).

It is time to embrace a biopsychosocial model for musculoskeletal pain.

British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(3), 149–150.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103524McGill, S.M. (2007).

Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation (2nd ed.).

Human Kinetics.Vos, T., et al. (2021).

Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis.

The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9Dankaerts, W., et al. (2006).

Differences in postural control between subjects with low back pain and healthy individuals during sitting.

Spine, 31(6), 682–689.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000200759.31775.02Leeuw, M., et al. (2007).

The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence.

Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(1), 77–94.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0